An exercise: How might voting districts affect the current city council?

A proposal to divvy up Vancouver into three voting districts fell flat at city council last week. Councilors declined to move forward with a recommendation that they put the question of establishing districts on the November ballot.

A little background: The change would draw boundaries lines around three as-yet-to-be determined districts, and voters in each district would elect two city councilors. Candidates would first square off in primary elections within those districts and then advance to an at-large general election. The change was marked as the No. 1 priority for the Charter Review Committee during its five-year review of the city’s governing document. Establishing districts would help create a more diverse council geographically, racially and economically by drawing representation from underrepresented populations in Vancouver, the charter committee argued.

The council disagreed, 4-2. Erik Paulsen and Laurie Lebowsky, the two newest members on the council, expressed a willingness to move forward with districts. Bill Turlay, Bart Hansen, Linda Glover and Ty Stober opposed them.

“Could this in fact be a bit limiting?” Glover asked at last week’s meeting. “If they happen to live in the same district, we’ve lost that resource.”

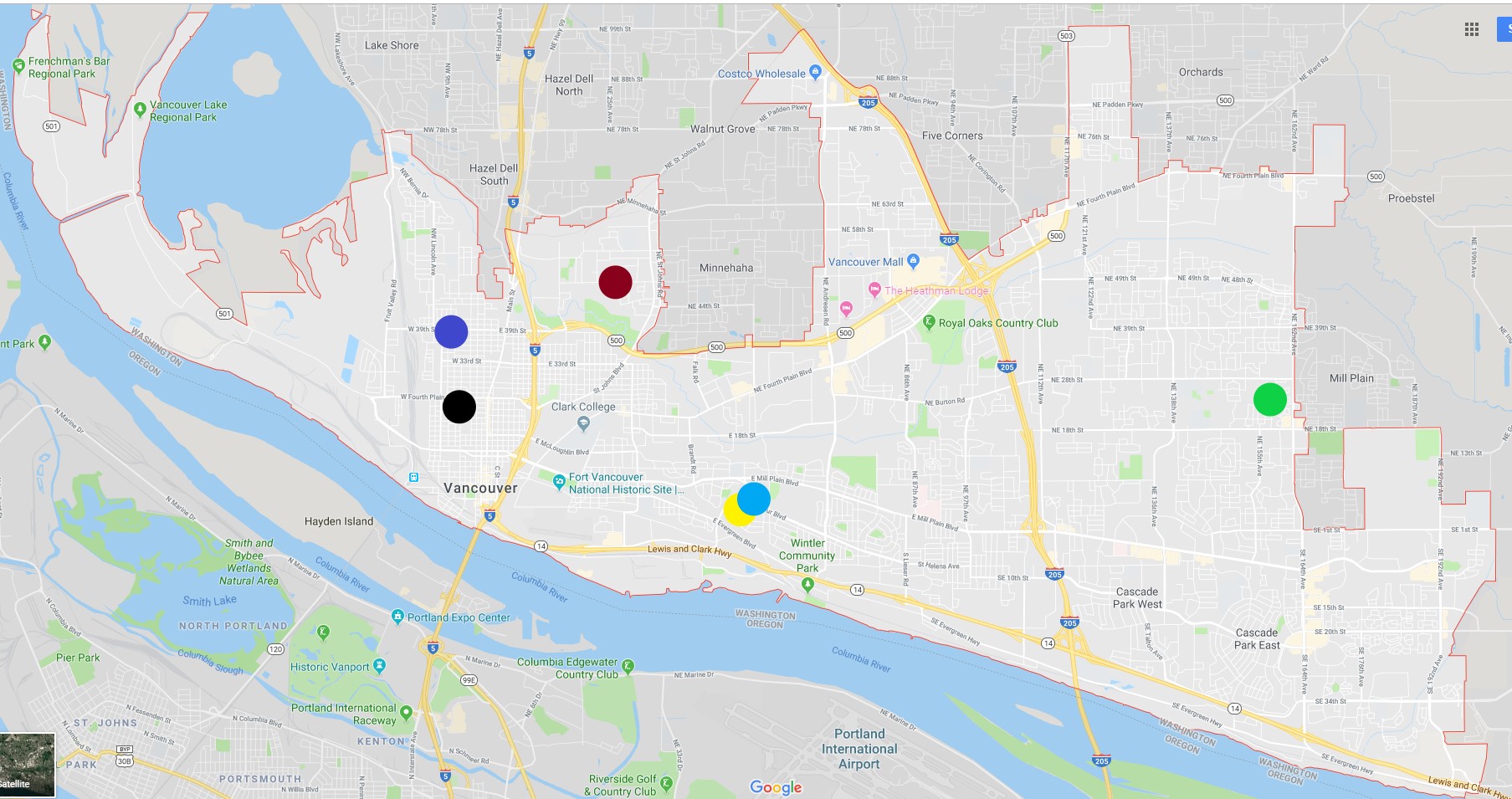

I wondered how a districting proposal might affect the current city council. Where do they live? Would any incumbents end up running against each other? Do they personally have anything to lose by advancing electoral districts?

The current councilors live in:

- Lincoln (Lebowsky)

- Hough (Stober)

- West Minnehaha (Hansen)

- Dubois Park (Glover)

- Dubois Park (Paulsen)

- Burton Evergreen (Turlay)

We don’t know exactly where the district lines would have been drawn, so this exercise is speculative. But let’s indulge a few districting scenarios.

Say the districts divided Vancouver as simply as possible, into three vertical chunks: West of I-5, between I-5 and I-205, and east of I-205. That division would see Lebowsky and Stober on the west side, Hansen, Glover and Paulsen in the central district, and Turlay on the east side.

Say the districts sliced up Vancouver horizontally: North of West 39th Street, Highway 500 and NE Fourth Plain Boulevard; between 39th/500/Fourth Plain and East Mill Plain Boulevard; and south of Mill Plain. That would put Hansen in the northernmost district, Turlay, Lebowsky and Stober in the central district and Paulsen and Glover in the south.

Neither of those options makes much sense, though, if the goal is to divide the city into districts that are a.) roughly equal in population, and b.) designed to promote diversity on the city council.

A scenario that would better align with the goals of districting: one L-shaped district that includes downtown Vancouver and extends southeast to include wealthy neighborhoods along Highway 14; a second district that encompasses north central Vancouver and the I-205 corridor; and a third district that stretches across the entire east side of the city.

This scenario would also force more competition among incumbents. Lebowsky, Stober, Glover and Paulsen would compete for two seats in this L-shaped district along I-5 and Highway 14. Hansen would be alone in north-central Vancouver. Turlay would be alone in the east.

Again, this exercise is hypothetical. Districts, like any changes to the city charter, would require multiple steps. First the city council would need to change course and ask voters on a general election ballot whether or not to divide into districts. Then voters would need to vote ‘yay.’ After that, the council would need to appoint a districting commission, who would draw district boundaries after a much more comprehensive look at the demographics and population of Vancouver. After all that, we’d know which incumbents end up in the same district.