Word War Winners!

We know this blog is meant to be about local politicians, but we are going to write about ourselves today because we triumped in the inaugural Word War on Saturday. Myself and fellow mavens Marissa Harshman and Eric Florip called ourselves Inverted Pyramid, donned some handmade puff-paint T-shirts and wrote a winning story.

We triumphed over four other teams, including one made up of intense, hipster librarians named Unrelenting Onslaught.

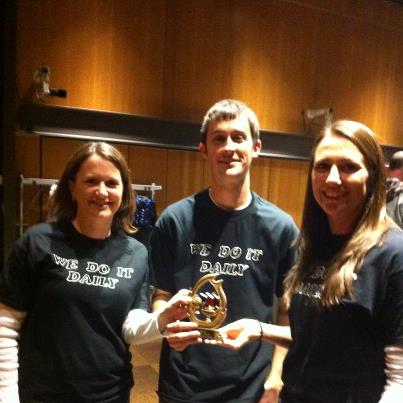

Here we are with our trophy Saturday at Vancouver Community Library. Our T-shirts say, “We Do It Daily.”

Here we are with our trophy Saturday at Vancouver Community Library. Our T-shirts say, “We Do It Daily.”

We’re talking about the fact we write for a daily newspaper, of course.

Each team was given the same four prompts that had to be incorporated into a story. Broadsheet 360, which put this event together, came up with the prompts. We received our first prompt at the library, then walked to three downtown businesses — Gouger Cellars, Torque coffee and Salmon Creek Brewery — and at each stop we received a beverage and another prompt. The prompts were: writer whose fingers are bloody from the keyboard, a free-range urban chicken on the loose in the city; bridge to nowhere; and a Vancouverite with a mullet and cut-off jeans.

Armed with Marissa’s laptop, we discovered that we work well together and that writing is more fun when you do it while drinking. We were also glad that beer was our last stop, as teams were sent to the locations in different orders. We were the first team to turn our story in, and we came in well under the maximum of 1,500 words. As reporters, we know that longer isn’t always better.

Armed with Marissa’s laptop, we discovered that we work well together and that writing is more fun when you do it while drinking. We were also glad that beer was our last stop, as teams were sent to the locations in different orders. We were the first team to turn our story in, and we came in well under the maximum of 1,500 words. As reporters, we know that longer isn’t always better.

The stories were judged by the local dudes, documentary filmmaker Beth Harrington and poet (and, unbeknownst to us, lover of the Old Apple Tree) Scott Poole. Our award-winning story is below, but first I’ll give you a close-up shot of the award. So cute! (The intense librarians had to settle for second.)

He had to admit, the casket looked good.

A woman with an angelic voice was singing “Amazing Grace,” but Vern McDonald wasn’t focused on her. His mind was somewhere else. For the first time, he reflected on what had been his craziest week since taking the city manager job two years ago.

As it turns out, building the casket was the easy part. His parks director Ron turned out to be quite the wood craftsman.

But getting the city council to agree to cut down the beloved Old Apple Tree to build the casket, that took some work.

His mind drifted back to the funeral, where the director of the Clark County Historical Museum was eulogizing Esther, longtime city council member and unofficial town historian.

Vern winced as he remembered hearing Esther’s dying wish: to be buried in a casket fashioned from the Old Apple Tree.

He knew it would be a fight, but he wasn’t prepared for the opposition’s fierce loyalty to the tree. When he looked at the decrepit tree, cordoned off with a chain-link fence, he saw a tree on life support, kept alive in a vegetative state. But certain members of the city council and a few longtime residents were playing the roles of relatives unable to pull the plug.

He glanced down at his fingers, which a few days earlier had been bleeding on his keyboard after feverishly writing letters to plead his case. One councilor, in particular, hadn’t seemed to track what was going on. She kept calling him to complain about a free-range urban chicken on the loose in her Rose Village neighborhood.

After her fifth call about the chicken, he reminded her that the city contracts with Clark County Animal Control. “Call them,” he had told her.

And then there were the gadflies who came to every meeting to complain about a project the city had no real authority over. They’d been making their case for nine years now, undeterred by the fact that the project — they called it the “bridge to nowhere” — was gaining the favor of the state and federal agencies that held real sway. Vern had long since memorized their arguments. But there they were, every single week, perhaps under the impression that repetition was their strongest rhetorical weapon.

Vern shook himself out of it. He looked toward the front of the funeral chapel, where the mayor was now speaking and had somehow made the gathering more about himself than Esther. No one was sure how long he would be speaking. And for once, what he was saying wasn’t Vern’s problem.

He looked back at the casket, which really was a work of art, given what Ron had to work with. He finally had gotten a majority of the council to agree that Esther’s final wish should be granted by promising that a new apple tree would be planted and the councilors’ names engraved in the trunk.

He even had to agree to the urban forester’s ridiculous idea to pay respects to the old tree. About a dozen residents dressed in black came to the gathering. A steady drizzle fell as they gazed at the tree’s gnarled boughs one last time.

Tears ran down the urban forester’s face as he looked at his life’s work. Then he yanked the rip cord of the chainsaw. As it rumbled to life, a few turned away. They couldn’t bear to watch.

One councilor, a retired Army colonel, played “Taps.” Vern rolled his eyes. Maybe his wife was right. Maybe he should have stayed in the private sector.

The tune had been interrupted by the sound of a car door. Vern turned his attention to the baby blue El Camino parked on the grass. A Miller Lite can fell to the ground as a 40-something Vancouverite with a mullet and cutoff jeans emerged from the car. He stumbled toward the gathering and hollered, “That firewood for sale?”

Vern sighed. This is his life.

He turned his attention back to Esther’s funeral. Mourners were making their way to the front of the chapel to say their goodbyes. Ron smiled as he ran his finger along the smooth edge of the casket, clearly admiring his craftsmanship.

Vern still couldn’t believe that in eight hours Ron turned the mangled tree into a thing of beauty.

When it was Vern’s turn to walk past Esther’s body, he looked down and thought about her wish. Despite the obstacles, Vern was happy he could make her wish come true. If only she could see the casket herself.

Vern thought about the weeks before taking the job, when he had sought advice from Esther. She warned him that he would be asked to do things he never imagined. So it’s fitting she ended up presenting him with his biggest challenge yet.

As Vern walked out of the chapel, he was relieved to have time to decompress. Tomorrow was Monday, which meant another city council meeting, another set of headaches, another appearance by the gadflies.

Vern entered his office Monday morning still feeling drained from the events of the past week. His assistant walked up to him, handed him a letter and said it was from Esther’s daughter.

He peeled back the envelope flap and removed the letter. He recognized Esther’s handwriting. On the crinkled piece of paper were six words: I knew you could do it.

Vern’s assistant popped her head into his office. “Councilor Ferris is on the phone. She wants to talk about the chicken.”

Vern smiled. “I’ll take it.”