Feline Pancreatitis

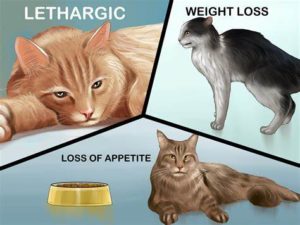

Pancreatitis — inflammation of the pancreas – is relatively rare, but recognizing its signs early is essential to any cat’s health. These signs can include lethargy, increased thirst and urination, poor appetite or refusing to eat, dehydration and weight loss.

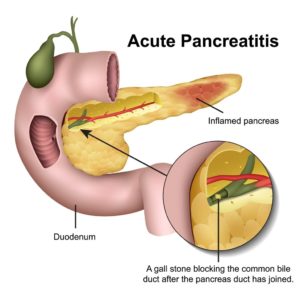

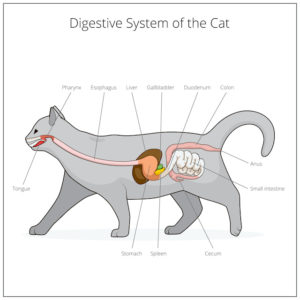

What then, is the pancreas? A small organ tucked between the stomach and intestines, it plays a vital role in producing the hormones, insulin and glucagon, which regulate blood sugar. It also produces digestive enzymes that help break down carbohydrates, protein and fat.

While the precise cause of most cases of feline pancreatitis isn’t known, it’s been associated with a cat’s having ingested toxins, having contracted a parasitic infection or having suffered a trauma such as a car accident. And it’s commonly divided into two sets of categories: acute or chronic, and severe or mild. Ironically, there’s a disparity between the number of cats with this condition and those who are actually diagnosed and treated. Why? Cats with mild cases may show few, if any, symptoms, while symptoms that don’t seem disease-specific may not warrant a visit to the vet. And because feline pancreatitis is difficult to definitively diagnose without a biopsy or ultrasound, many cat owners forgo these tests because of the cost.

There are, however, other less expensive diagnostic tools available. One is the serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI) test, a non-invasive blood test that looks for markers of pancreatitis. Another, the serum feline trypsin-like immunoreactivity (fTLI) test, may not be as reliable as the fPLI test, but it can help identify exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, a disease that cats with chronic feline pancreatitis can also develop.

Posing the most serious risk to your own cat’s health is acute feline pancreatitis, and it usually requires hospitalization. Depending on its severity, chronic pancreatitis may call for periodic trips to the hospital but it can usually be managed at home. At the hospital, your cat will receive intravenous (IV) fluids to address her dehydration and, if warranted, detoxify her pancreas from any damaging inflammatory toxins. She may also be given antibiotics to minimize her risk of developing suppurative (infectious) pancreatitis, as well as painkillers and an anti-nausea medication to help combat any nausea she might have.

Once back from the hospital, it’s recommended that she be fed appetizing and easily digestible food as soon as possible provided she’s hungry and isn’t vomiting. Comforting her plays an important role in both making her feel safe and helping her to regain her appetite. If, however, she seems queasy and has difficulty eating, your vet may recommend an antiemetic to decrease her nausea and control any vomiting she might have. But if she’s vomiting frequently and isn’t at risk for fatty liver disease, your vet might suggest re-introducing food to her over a period of several days.

Cats unable to eat on their own may require a feeding tube. With a variety of options available, your vet will discuss the best one for your cat and teach you how to use it. Despite their intimidating appearances, feeding tubes are relatively easy to use, gentle on her, and essential in delivering the food, water and medications she needs during her recovery.

Whereas severe cases of feline pancreatitis require hospital stays and specialized care, many forms of this condition are mild and non-threatening. Learning to recognize the warning signs, then acting swiftly is the best way to ensure that your cat lives a long and happy life.