New look at artificial sweeteners

Foods sweetened with artificial sweeteners may not be a guilt-free way to enjoy treats after all.

New research suggests artificial sweeteners may change the microbes living in our intestines, which can then affect blood-glucose levels.

Researchers curious about how various sweeteners impacted the microbes living in the human intestine began by looking at the impact to mice, according to the National Institutes of Health.

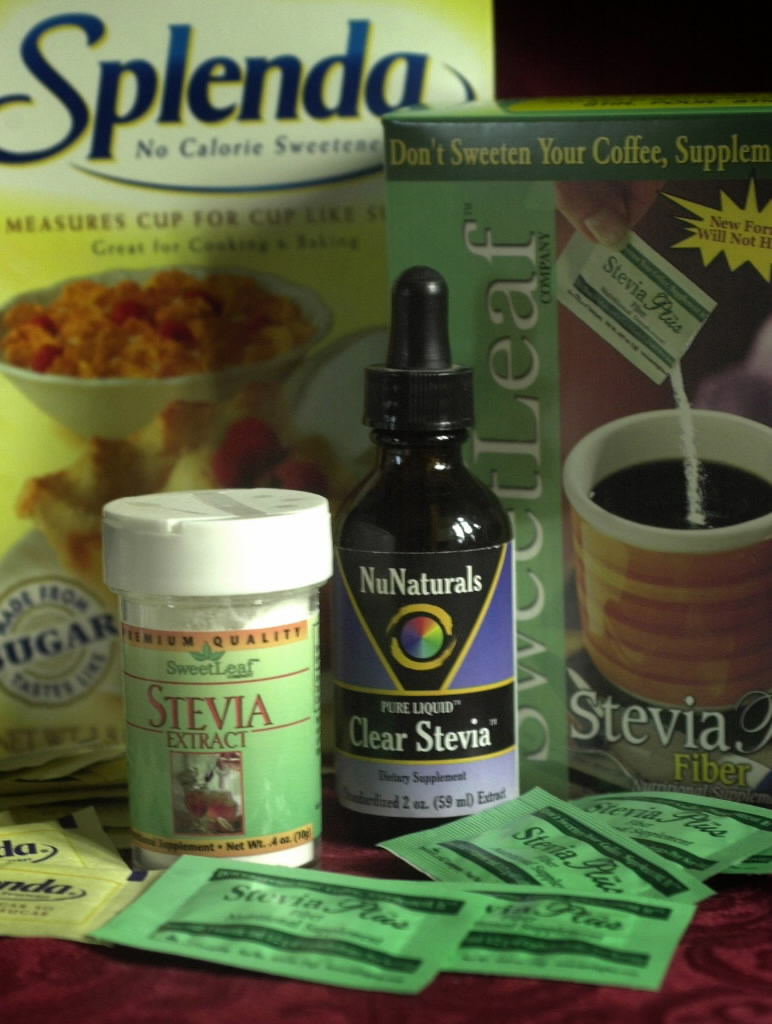

Researchers gave one group of mice water that contained a natural sugar (glucose or sucrose) and another group of mice received water that contained an artificial sweetener (saccharin used in Sweet’N Low, sucralose used in Splenda or aspartame used in Equal and Nutrasweet).

Researchers discovered many animals in the artificial sweetener groups (especially those in the saccharin group) developed glucose intolerance, which is characterized by high blood-sugar levels and is a warning sign for Type 2 diabetes.

The mice that drank sugar water remained healthy, according to researchers.

The researchers analyzed the artificial sweetener group’s gut microbiome and found a distinctly different collection of microbes than in the mice that drank sugar water.

The researchers used antibiotics to wipe out the gut microbes of the artificial sweetener group and the blood-sugar levels returned to normal – evidence the microbes were causing glucose intolerance, according to researchers.

Next, the researchers looked at humans.

Researchers looked at clinical data from 400 people in an ongoing nutritional study. They found that, compared to people who didn’t consume artificial sweeteners, long-term consumers of artificial sweeteners tended to have higher blood-glucose levels and other indicators associated with diabetes and obesity, according to researchers.

The researchers then asked seven people who had never consumed artificial sweeteners to consume the maximum dose of saccharin allowed by the Food and Drug Administration for six days.

Four of the seven volunteers developed glucose intolerance. The other three maintained normal blood-sugar levels.

Researchers transplanted the microbes from the people to germ-free mice. The microbes from the humans with glucose intolerance triggered glucose intolerance in the mice, but the microbes from humans with normal blood-sugar levels had no effect on the mice, according to researchers.

The results of the study must still be confirmed in larger studies.