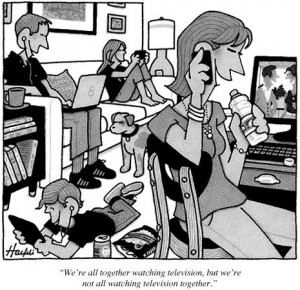

Children watching parents watching screens

We all know, having read a Columbian masterpiece on May 18, just how cool Vancouver’s downtown has grown these days.

I noticed another aspect of downtown cool – unless maybe it’s downright cold – during an afternoon stroll around what some like to call Vancouver’s living room. (And living room is another name for “family room,” right?)

There were four little family units enjoying the sunny Esther Short Park playground at about 2 p.m. Happy kids were clambering on the equipment and racing around the wood chips.

Meanwhile, four parents were perched separately on the four concrete borders of the play area, deep in cyberspace. Each frowning at a hand-held device. Heads down. Eyes on electrons. I waited a minute to see if anybody might snap back to reality, notice a kid and crack a smile, but none did. Grownup attention was firmly fastened to screens. It was the kids who did all the enjoying of life.

This is so mundane, who even notices?

Kids notice. Last year the journal Pediatrics published a study that concluded the obvious: children learn behaviors from parents, and parents who stare at screens will raise children who stare at screens.

And children who stare at screens for more than two hours a day (and show me the child who doesn’t) tend to run a greater risk of obesity, poorer school performance, increased aggression and depression. That’s according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, which sites several large studies that followed the screen-watching habits and health of children across decades.

Earlier this year I did some reporting about early childhood education – at school and at home – and the way it sets lifelong patterns. And I also took a look at the teen brain which, according to recent science, seems to get a second chance during a period of intense pruning, regrowing and reconnecting of internal wiring.

So, the choices kids make – and that parents sometimes must and do make for them – make a difference, no matter whether early or later.

“Adolescents who get involved in service learning learn that that’s normal and good. That’s what’s hooking up in the brain,” Kathy Bobula, who just retired from teaching psychology and early childhood education at Clark College, told me. But adolescents “who play video games all day, who just satisfy their transient desires all day, well, that’s what’s hooking up in the brain. They sure get good at that,” she laughed. “They develop great thumb control and eye-hand coordination and they’ll probably grow up to be great bomber pilots.

“But that’s at the expense of deeper thoughts and conversations, moral choices, relating to people,” Bobula said.

As AAP spokesman and University of New Mexico professor of pediatrics Victor Strasburger said: “There is a displacement effect. If you are spending seven hours with media, those are hours you are not walking the dog, playing on the soccer team or hanging out with friends.”

And if you’re the parent, they’re hours you’re not enjoying your kid – and setting a positive example. You won’t get them back.