Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) in Cats

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is caused by a coronavirus unique to cats and isn’t contagious to people, dogs or other animals. Spread, in most instances, through contact with feces, this virus typically lives inside a cat’s intestinal tract.

The majority of cats are exposed early in their lives to the organism causing FIP — sometimes from their mothers – and while almost all of them carry the organism, it’s believed less than 5% actually go on to develop FIP. Most cats who develop FIP are between three months and two years of age, although cats of any age can develop it. Not only does the disease require a specific interaction between a cat’s immune system and a mutated form of the organism, but it’s also, sadly, the main reason there’s no reliable diagnostic test for the disease. In fact, FIP is one of the least understood of all cat diseases.

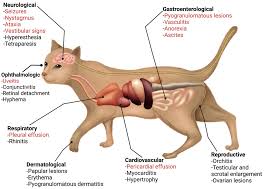

Typically diagnosed through a process of elimination, cats suffering from FIP may present with a variety of symptoms from several other conditions such as abdominal tumors, toxoplasmosis or an infection with mycobacterium. To complicate matters further, a cat’s symptoms will also depend on which organ or organs are affected, since FIP can negatively impact the liver, kidneys and pancreas, not to mention other organ systems, ranging from the eyes to the abdomen to the central nervous system.

Most infected cats begin exhibiting signs of the illness by eating poorly, running a fever and/or behaving lethargically. There are two forms of FIP: Wet (or effusive): this causes bloating and swelling in the abdomen (ascites) and may also affect the heart and lungs. Cats with this form of the disease may pant and seem sleepy and droopy. Dry (or non-effusive): this usually affects the eyes (many cats will go blind) and causes such neurological symptoms as problems with balance and seizures. Cats with no immune response develop wet FIP, those with a partial immune response develop dry FIP, and some actually show symptoms of both forms of the disease.

Respiratory transmission, while possible, is less common. But because the traditional route of infection is contact with infected feces from litter boxes, cats living in a multi-cat household and who may share litter boxes are the ones most at risk. And yet, developing the disease requires a specific interaction between the virus and their immune systems. It’s not uncommon, then, to see one cat die of FIP and the others remain healthy.

Although vets can easily diagnose “wet” FIP by drawing a sample of fluid from the affected cat’s abdomen for analysis, other cats may require additional testing to rule out other possible diseases, leaving FIP as the likeliest culprit. And because FIP is almost always fatal and has no specific cure, vets can, at this point, only offer them supportive care. Anti-inflammatory drugs such as corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone) along with specific drugs that suppress the immune system (e.g., cyclophosphamide) may both extend their lives and improve their quality of life.

Several experimental drugs, currently being investigated for use in the battle against FIP and not yet approved by the FDA, include one known as GS441524 or simply GS441. Expensive, stressful for owners and cats, and not always successful, it requires stringent monitoring and dosing for a period of 84 days, and is available in both injectable and pill form. (The costs and dosages vary depending on the weight of the infected cat). The goal is for the cat to remain symptom-free upon completing the treatment for an observation period of another 84 days.

While a vaccine for feline coronavirus exists, it has its limitations. First, it’s only approved for kittens older than 16 weeks of age. And second, vaccinating cats in multi-cat households may be ineffectual since feline coronavirus is so common that most of them will be infected by the time they’re old enough to receive it. For these reasons, the American Association of Feline Practitioners does NOT recommend routine usage of the FIP vaccine.