Cardiomyopathy in Cats

Cardiomyopathy, simply put, refers to a “disease of the heart muscle,” specifically the myocardium.

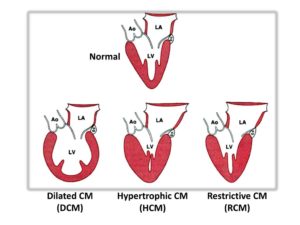

It’s a condition caused by a structural abnormality in one or more of the four chambers of the heart, most commonly the left ventricle. The muscle involved becomes too thick, either scars and stiffens or weakens, thereby impairing the heart’s ability to pump blood.

Feline cardiomyopathy is considered a primary disease and consists of three types: hypertrophic, restrictive and dilated. It mainly affects adult cats, and while all cats are susceptible to the disease, some breeds are genetically predisposed to it.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the most prevalent type, is characterized by a thickening of the left ventricle which prevents the heart from relaxing normally when it fills with blood. This can, over time, lead to elevated pressures within the heart, ultimately resulting in congestive heart failure (fluid accumulation). Some cats may also have a significant heart murmur while others may have none. To confirm a diagnosis of HCM requires an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) that demonstrates a thickened left ventricle with no identifiable underlying cause for the changes detected.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) results from an excessive buildup of scar tissue (fibrosis) on the inner lining of the ventricle. This prevents the ventricle from properly relaxing, filling and emptying with each beat of the heart, and, as with HCM, requires an echocardiogram to confirm it.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), seldom seen today, was linked historically to a dietary taurine deficiency — since corrected by most manufacturers of cat food. This condition is characterized by a poorly contracting, dilated left ventricle, and is often accompanied by enlarged atria, generally resulting in congestive heart failure.

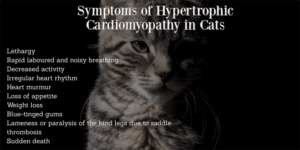

While cats with feline cardiomyopathy can remain asymptomatic for years, many will, at some point, start exhibiting clinical signs associated with their disease. The most common one is congestive heart failure, and the most common location for this buildup of fluid is in their lungs (pulmonary edema) or around their lungs (pleural effusion). This makes breathing extremely difficult and constitutes a true medical emergency.

As for treatment: In cases where an underlying cause of a cat’s cardiomyopathy is found, treatment may result in either an improvement or a reversal of the disease. The most treatable underlying cause is hyperthyroidism where complete resolution is possible if diagnosed and treated early. In cases with no clearly identifiable underlying cause (idiopathic cardiomyopathy) or where the disease persists despite having treated the underlying cause, medication may then be needed, and can include:

- Diuretics: If congestive heart failure is present, diuretics help reduce any fluid accumulating in the chest.

- Beta-blockers: These reduce the heart rate if it’s excessive.

- Calcium channel blockers: These help the heart muscle relax thereby allowing the heart to fill more effectively.

- Aspirin: This may be used to reduce the risk of the formation of blood clots, but since aspirin can be toxic to cats, always follow your vet’s dosing instructions.

- Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: These drugs also help control congestive heart failure.

- Blood pressure lowering drugs: These treat hypertension.

The long-term prognosis for cats with cardiomyopathy depends on its cause, while cats with idiopathic cardiomyopathy can stay stable for several years.