Cat tails, car rides, and the fear of failure

W hen he opened the hood of the car, and reached his hand deep inside the front of the car, his face contorted, and we all knew something wasn’t quite right. When we saw his hand gripping a calico tail, we all assumed it would be okay, but when only the tail emerged from the engine, and we heard the frantic, high-pitched yawps, everything changed. By the time the tow-truck truck arrived, my grandpa finally stopped fishing for the rest of the cat — which had become mysteriously quiet.

hen he opened the hood of the car, and reached his hand deep inside the front of the car, his face contorted, and we all knew something wasn’t quite right. When we saw his hand gripping a calico tail, we all assumed it would be okay, but when only the tail emerged from the engine, and we heard the frantic, high-pitched yawps, everything changed. By the time the tow-truck truck arrived, my grandpa finally stopped fishing for the rest of the cat — which had become mysteriously quiet.

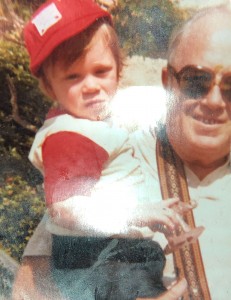

I was seven, we were on our way to Disneyworld, and this would become my only memory of my Grandpa Robby. He lived in Florida, and we were all the way on the other side of the country in Portland. There weren’t many visits that direction. I don’t recall how they retrieved the dead cat from the engine compartment, or if we were even able to continue driving that car. I do know we eventually made it to Disneyworld, and I’ll assume that I had a wonderful time, but I have absolutely no memory beyond that car ride.

My grandpa had failed. He failed to notice the cat prior to starting the car. He failed to complete the drive without incident. He failed to pull the cat — at least the body — from the engine. The success, however, was creating a memory that would last me a lifetime. Sometimes failure works out. Sure, the cat died, but despite the adversity, we eventually made it to our destination. The fact that I do not remember being upset, I do remember laughing at the absurdity, which even at only seven I understood. My family believes heavily that joking about difficult situations can make even the most devastating moments easier to stomach.

We all experience the moment where the cat screams for the last time. We have all lost our proverbial tail. It’s how we deal with the situation that matters. It’s the student that keeps moving the pencil on the paper, or who looks at the FeedForward from their teacher, and discovers an alternative pathway to the right answer, or to motivation, or to finally turn in an assignment, show up for class, master the standard, create a masterpiece, decide on their future.

As educators, we are taught that to fail is simply the first attempt at learning. In Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, she talks about the first draft as the vomit that spills over the floor. The second draft is when you grab the cleaning supplies, get down on your hands and knees, and start to sop up the chunks of last night’s meal. The final draft is when the floor is so clean you could eat from it. This analogy works well with the idea of failure. A first draft, as Lamott would say, is supposed to be a “shitty first draft”. We are not meant to succeed on our first attempt. If we keep in mind — as people, as teachers, as students — that we can glean insight from our attempts in learning, we can begin the revision process. We can plan for the next draft, or the next attempt at the necessary standard, or learning target, or goal.

I used to have a hard time with this concept. Why on Earth would I want to tell a student that they have failed to meet their goal. We grew up thinking that failing means finality. If, as a student, I failed an assignment, my grade in the class would be ruined, and I would simply have to deal with the fact that I obviously didn’t try hard enough, or pay enough attention, or didn’t understand the material. Instead of teachers working with me to better my skill set, further understand the work needed, or offering me an attempt to redo the assignment, they would tell me — as I told far too many students — that the grade was in the grade book, and unless I built a time machine, there wasn’t much I could do about it. When I realized how incredibly detrimental this was to me, I quickly realized that I was doing the exact same thing to my students. I was more concerned with the time I’d spend grading their redo than I was helping them learn how to actually complete the work properly. My garbage can sat in the corner of my classroom with a sign above it that stated, “To be graded this summer”. If you turned in a late assignment, I would point to the corner as a reminder that I wouldn’t accept it from them. They had failed, and that was that.

Until it wasn’t.

When I finally wrapped my head around the idea that students might fail, I realized that it wasn’t because they didn’t try. In fact, it was because I didn’t approach it properly. I didn’t remind them that everyone fails once in a while, and that if they worked hard on x, y, and z, they could revive their failed attempt, and move toward proficiency, if not mastery. More importantly, they can move toward confidence. They can begin to better themselves. I learned that failure happens. They already knew that. I learned that it wasn’t all about my time, but rather their knowledge, their passion, their attempts in learning.

Grandpa Robby passed away not too long after this trip, and while I don’t remember any other time spent with him, that calico cat tail acts a reminder that sometimes we — or animals or students or teachers or people — fail. Sometimes we choose the wrong path, or sometimes our tail is yanked from our bodies after choosing the wrong place to seek shelter from the heat. While the cat didn’t survive its first attempt in learning to avoid engines, we can all take a moment to look at our work, or the dead cat, figure out how to connect the pieces, and keep driving to Disneyworld.

Follow Chris Margolin on Twitter at @theEDUquestion