Are anti-oil train signs protected speech?

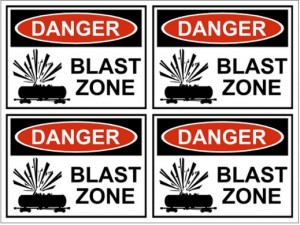

A group of a dozen or so community leaders and activists opposed to the oil-by-rail terminal proposed for the Port of Vancouver have taken their campaign to the streets with signs that say “Danger: Blast Zone.”

A group of a dozen or so community leaders and activists opposed to the oil-by-rail terminal proposed for the Port of Vancouver have taken their campaign to the streets with signs that say “Danger: Blast Zone.”

The anti-oil train campaign placed signs along the railroad tracks next to Fruit Valley Road and Lakeshore Avenue, where Vancouver and unincorporated Clark County meet.

Several mile-long unit trains loaded with highly volatile Bakken crude are already traveling that route daily.

Clark County code enforcement told the campaign the signs violate the rules and must be removed, while the city of Vancouver deems the signs to be protected political speech.

Paul Scarpelli, who heads Clark County’s code enforcement office, said campaigns wishing to place political signs must file an application with the community development department. The county received “a basketful of complaints” — which he clarified to be four — about the oil train signs. People who hope to sell their nearby homes were among those who objected.

Scarpelli said the signs are not political speech because there’s no ballot measure about oil trains before voters. Further, he said, the design violates a state law that prohibits signs “simulating directional, warning, or danger sign or light likely to be mistaken for such a sign or bearing any such words as ‘danger,’ ‘stop,’ ‘slow,’ ‘turn,’ or similar words.”

Chad Eiken, Vancouver’s development overlord, said his department turned to the city’s legal team. “Their position is that the anti-oil train signs are political signs and can’t be removed unless they violate our guidelines,” he said. “In their opinion, it’s a matter of free speech under the First Amendment.”

The Vancouver City Council has gone on record opposing the $210 million oil terminal proposed by Tesoro Corp. and Savage Companies, which would handle an average of 360,000 barrels of oil a day.

Vancouver resident Linda McLain, one of the organizers of the anti-oil train campaign, said the group has “no problem with the county.” The campaign placed only five or so signs outside city limits and those have all been stolen, she said.

“We have had approximately 200 signs stolen out of the 250 we bought. It is very bizarre — we put them up and within hours they are gone,” McLain said. “There’s obviously someone who doesn’t want those signs up.”

The campaign is a small group of people from all walks of life, according to its web site, which is deliberately vague. But these are the people who show up during the port commission’s public comment period to voice their opposition to the oil terminal project, said McLain and another organizer, Michael Piper. They contributed $1,200 of their own money to buy the signs.

Piper takes credit for the idea, a tactic he said he swiped from his days with Greenpeace opposing the so-called “white trains” that carried nuclear material.