CDC issues guidelines for opioid prescribing

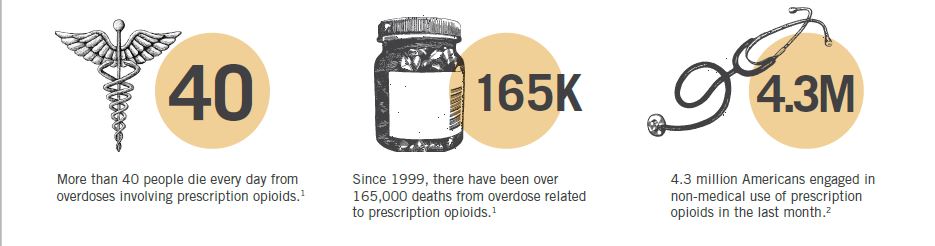

The number of opioids being prescribed and sold in the U.S. has quadrupled since 1999.

In 2013, health care providers wrote 249 million opioid pain medication prescriptions – enough for every adult to have a bottle of pills.

And every day, 40 people die from overdoses involving prescription opioids.

In response to the prescription opioid epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control today issued new recommendations for prescribing opioid medications for chronic pain, excluding cancer, palliative and end-of-life care.

“Overprescribing opioids — largely for chronic pain — is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, in a news release. “The guideline will give physicians and patients the information they need to make more informed decisions about treatment.”

The 12-point guideline aims to improve the safety of prescribing and curtail the harms associated with opioid use; focuses on increasing the use of other effective treatment options for chronic pain; and offers providers specific information on medication selection, dosage, duration and how to reassess the progress, according to the CDC.

Here are the new guidelines:

1. Opioids are not first-line therapy. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy – medications such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, exercise therapy, weight loss, behavioral treatment, interventional treatments such as injections – are preferred for chronic pain.

2. Establish goals for pain and function. Clinicians should only continue opioid therapy if there is a clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks.

3. Discuss benefits and risks before starting and periodically during opioid therapy.

4. Use immediate-release opioids when starting opioid therapy, rather than extended-release or long-acting opioids.

5. Use the lowest effective dose. Clinicians should carefully reassess benefits and risks when increasing dosage to more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day and should avoid increasing dosage to more than 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day.

6. Prescribe short durations for acute pain. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. Clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose and no greater quantity than needed. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.

7. Evaluate benefits and harms frequently. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms for chronic pain at least every three month.

8. Use strategies to mitigate risk, such as offering naloxone when there are factors that increase the risk for overdose.

9. Review prescription drug monitoring program data when starting opioid therapy and periodically during therapy for chronic pain.

10. Use urine drug testing. Clinicians should use drug testing before starting therapy and at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Avoid concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine prescribing.

12. Offer treatment for opioid use disorder.