Ghosts play with workers at Vancouver Barracks

Story provided by Vancouver historian and ghost hunter Jeff Davis, from his website at http://www.ghostsandcritters.com/

DATE: 21 August 2003

FROM: Hallie

SUBJECT: Vancouver Barracks

In the winter of ’01 I was working for a contractor repairing and restoring the windows in a number of the Vancouver barracks buildings.

The foreman told me about his experiences there, and though I wanted to see *something* I never really did. There were odd things that happened, though.

The building we set up as our ‘shop’ – where we stored our tools and supplies – was vacant and I can’t remember the number. (It’s been a while. There were the four barracks buildings that were occupied, and I remember the numbers for those – 987, 989, 991 and 993).

This was post-9/11, so they were fenced off with a guard shack controlling access to the area at that time.

There was another unoccupied building, number 607, that we also worked on.

614, the hospital building, was originally in the contract, but was dropped for lack of funding toward the end. I couldn’t tell if I was disappointed or relieved, because we’d all heard stories about the morgue hauntings and felt the general creepiness.

Our shop building had a fire alarm system in it. It was always making odd beeping sounds that could never be remedied by the maintenance guy, who’d tried over and over to make it work properly.

One day, early on in the summer of ’01, the foreman – who was one of only two people on the job at that point – was working late on the second floor of the building. His partner – who got a creepy feeling in the basement of that building and thereafter refused to go downstairs – had already left.

He’d put in a call to the maintenance guy to come out and see about the freaky fire alarm system. As a carpenter, you make a racket when you work, so he’s pounding away, tearing the windows out, and pauses in his work long enough to hear footsteps across the floor.

Now, the building is vacant – wide open – grade school tiled floors and vast, empty echoey rooms. Stray school desks here and there, but not much going on. The paths through the rooms get a little labyrinthine in places, but several rooms are the size of cafeterias – with no more than two plainly visible and distant exits and nowhere to hide. Other rooms are bedroom sized, but completely bare.

He hears the footsteps and hollers, ‘hello!’ thinking it must be the maintenance dude. Nothing. Whatever – he goes back to work.

The footsteps again, and jingling keys. This sound is coming from the empty, cafeteria-sized room next to him, and very close. He peeks out there, and still hears the keys, the footsteps, but there’s no one there. The foreman left for the day.

He told me that the attic of that building had been used for indoor target practice in the winter in the 1800s.

The savagery of earlier centuries astounds me. Makes one grateful for video games, almost. He didn’t like it in the attic and spent as little time up there as possible. He mentioned that there were a number of accidental slayings up there as a result (duh) of young military men shooting firearms in close quarters.

Nobody liked it up there, especially since the lights didn’t work, for any electrical reason, and could not be made to work no matter what we did.

The fire alarm system never did calm down. As the low man on the totem pole of this job, I spent a lot of time cleaning up after the work, in the buildings alone.

We worked ten hour shifts in the winter time, which meant of course that it was dark when we arrived to work and dark again hours before we left. I would clean creepy-feeling rooms when it was light out and move to the ‘okay’ rooms as it got darker.

I wasn’t wild about it, but it all pays the same, you know? The basement that creeped out the other gal kinda bothered me, but I never saw anything in there.

The fire alarm would play with me, though.

I’d be alone, stamping windows with ID numbers or sweeping up, and it would beep crazily – beep beep beep beep beep beep – and then I would go over to the alarm system on the wall and look at it and the lights would be flashing like a Christmas tree, but no sound.

Then I’d turn away and it would beep and beep.

When I was cleaning, it would shriek at me intermittently, and then I’d turn the corner to go down to the basement and it would stop.

Then I’d look back round at the alarm and it would freak out again – beep beep beep beep beep beep. I don’t know if it was just messing with me or what.

Building 993 was by far the strangest feeling one of the lot. It was furnished and occupied in a completely different way than the others, too.

We got to hear a couple stories about the basement latrine, but I was too chicken to go down there.

By then I was starting to think that wanting to see something, back when I started the job, was a work of temporary insanity on my part.

One day a co-worker and I were in the tiny vacant barracks building just across the parking lot from the hospital. A couple of gals with clipboards and flashlights were going round through the buildings doing an environmental survey or something. We saw them from outside and waved at them through a basement window. They waved back. We went back to work.

A little later they came running back to the building asking for our help locating a phone because someone was dead in the hospital building and they wanted to call the police.

With a lot more aplomb than I myself could muster, my coworker mentioned that there was a teaching dummy in the building (Fort Vancouver has medical training gear around, even in the abandoned buildings) and did they know that?

He happened to know that the painter’s foreman was a jokester and used to have the resuscitation dummy hanging from a rope so that it would swing down in the path of whoever opened the front door. The hospital gets a lot of attention because of its reputation, and he wanted to deliver something exciting for the ghost hunters, I guess. I doubt he knew anyone was going to be up there on official business, since the building had by then been dropped from our contract.

The gals said no, no – there was a SMELL of death in the basement (morgue) of the building and that we should call the police.

They had started their survey work at one end of the hall and worked their way toward the morgue. They first saw a broken window, then beer bottles, then empty shotgun shells, and then the odor of death as they walked down the hallway.

Turning toward one of the rooms, they saw a pair of sweatpants-clad legs and ran screaming out of the building.

To make it sound even more like a Scooby-Doo cartoon, the lights to the basement didn’t work, and they had a hard time opening the front doors to get out.

Not wanting to phone in a fraudulent call, my coworker offered to go up there to check it out first. I went with him out of a sheer, terrible fascination.

He only told me later that he didn’t really want to go at all, but didn’t feel like he had much of a choice.

We went down there with an 18 volt flashlight and one of the two of the survey gals – the other refused to set foot in the place again and stayed on the porch.

We found all the evidence that they described, but the ‘body’ was indeed the resuscitation dummy, Annie.

There of course was no way to tell this the way the painter had arranged it.

They weren’t kidding about the smell of death, either, but it turned out that a squirrel had gotten into the basement (probably through the broken window) and couldn’t for the (literal) life of him find the way out – and he accounted for the smell.

A concrete pedestal at the Vancouver barracks Wednesday April 7, 2010. (The Columbian/Troy Wayrynen)

I didn’t like the feeling of that basement one bit and was glad as hell to leave, even though we hadn’t seen anything but the painter’s hoax.

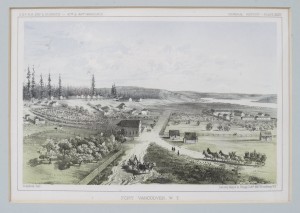

Something we were told about the hospital later, when we told this tale to the job superintendent, was that, during the war, bodies were stacking up faster than the morgue could process them.

Eventually, after the front porch and all available space was taken, they stacked the bodies out in a shed outside the hospital to await processing.

Even after it was over and the bodies were properly processed and disposed, and the shed torn down, nothing would grow there for ages. Eventually it was paved into the parking lot.